A reader wrote in to ask:

We have a new summer intern starting in a few weeks who I will be directly supervising. Although I have been the technical/project lead on various projects throughout my career, this is my first time having a direct report (even though it will be temporary!). I was wondering if you had any “go to” or favorite literature for managing in a technical setting.

Congratulations to them, and this is a great question. It’s such a great question that I’m disappointed to discover that I didn’t have handy resources to immediately share with them, and I’d love to hear what your recommendations are.

In research computing, probably the two most common ways people find themselves managing is to be promoted to lead their existing team, or the more gradual approach which is to start with one or more interns/co-ops/grad students/trainees/etc.

But very few of the resources we discuss in the newsletter - I maintain a small list here - are for this second case. Which is weird! A new intern or trainee for a summer is a really common starting point for a lead/manager, and it’s something I greatly encourage, for a number of reasons (like improving your hiring and onboarding pipeline.) But it’s different in key ways than managing a regular employee:

(By the way, I want to emphasize that last one. Interns WANT FEEDBACK. The last three co-op students I was responsible for mentoring, when we had a “first month review” - it’s in a checklist I share later on - all said that the thing they wanted more of was feedback and evaluation. They were high achievers, and are doing the internship to develop their skills. They craved knowing how they were doing and how to improve. If they didn’t hear that they were doing well, they worried they were doing badly. Don’t deprive your interns, or your full time staff, of feedback!)

Some of these things make managing an intern easier, or at least front loads the work (clear tasks) and some make it harder (much more junior). And of course because it’s often one’s first management responsibility, it’s harder still.

I asked around in the #research-computing-and-data channel of Rands Leadership Slack, and people their suggested (paraphrasing, to be consistent with the Chatham House Rules of that group):

All of which is excellent advice! This workplace stack exchange answer, is also useful.

For new managers of permanent full-time staff, I usually recommend three big things to focus on - one-on-ones (to build and maintain trust and lines of communication), feedback (to set expectations and keep people on track), and delegation (letting go of tasks).

But one’s probably not going to delegate huge chunks of one’s job to an intern (they won’t be there long enough and they probably have fairly well-defined work to do), and while one-on-ones are worth doing, you’ll probably be keeping a pretty close eye on their work, so the emphasis will be different. So my suggestions for starting with an intern would be to focus on two things, feedback and one-on-ones as a communication mechanism.

The usual one-on-one formula typically has some time put aside for the future/career development - I’d say if you want to make it a really valuable experience for the intern (and they will tell their classmates, which makes a significant difference when getting your next interns) one useful way to spend some of that time is, in the first few weeks, finding out what they want to be doing next, and then as they start accomplishing things, helping them express those as resume-friendly bullet points in a running list through the term, ideally with something they can show as a portfolio. It helps keep them motivated, and helps you know what’s important to interns these days which in turn helps you advertise for them better.

Also, towards the end (assuming of course you’re happy with how it went) if you sketch out a couple-paragraph letter of reference for them describing what they did and post that as a LinkedIn recommendation, that goes a long way too (and as a side effect leaves you with a record of what’s been accomplished, and a reminder about who they are in case they end up applying for a job in the future).

The other big thing is offboarding the intern. We all know this intellectually, but a recurring issue with short term team-members is making sure that whatever knowledge of what they’ve learned and created doesn’t disappear with them. Having a really robust plan for how they’ll document things, and verifying it repeatedly towards the end of their time with you is essential. We all say “well yes, of course” when that’s brought up, and yet we are all without fail surprised when they’ve left and something isn’t documented and no one knows how they’ve done something. Having some process involving them giving walk throughs, demos, talks, or whatever to someone on their way out both helps them with developing professional communication skills and helps you collect needed knowledge.

One way to approach this is to have a documented process for hiring, onboarding, supporting, and offboarding the intern. The first time or two through the process, it’ll be laughably off-base, and that’s fine. Once something is documented the process can iteratively improve over time, which is the key thing. It’s really hard to improve a process that isn’t documented. If it’s documented, you can update it through and at the end of the process.

To try to help, the question spurred me to clean up and make suitable for sharing a starting-point intern onboarding/support/offboarding checklist. It’s just a google doc checklist-style list of bullet points, and it geared towards a more project-based software development internship, but hopefully it will be useful to other intern managers as well.

So how about you, gentle reader? Do you have internship resources, tips, or advice for the reader who posed the question, or for the readership in general? Please let me know - just hit reply or email to [email protected].

With that, on to the roundup! It’s a bit short today, because it’s been that kind of a week.

Having Career Conversations - Joe Lynch

As I mentioned a couple of weeks ago, mentorship only goes beyond cheap advice-giving if you’re willing to dig in a little deeper to the questions and answers being presented to you.

Part of every manager and lead’s job is to support the career development of their team members. And that means having career conversations with them. That means digging deep. Lynch prods us to go beyond the superficial of what the team member says their goals are, and to understand the (usually multiple) motivations behind the goals. People, especially but certainly not only juniors, often trip over the XY problem in setting their career goals. They ask for help with X so they can do Y, when it’s not a given that Y is even what they really want, much less that X is the way to get it.

Beyond that, Lynch emphasizes:

Lynch gives a number of concrete suggestions, both tactical and more long term, for having these conversations, and if the topic is of interest it’s a short read.

We’ve talked about how candidate packets (e.g. #84) can be a useful part of the hiring process — that documents are posted about the job and hiring process, either (ideally) publicly or as something that every candidate who makes it past initial screening (say) gets. This is a great way to make your organization look more together (and thus more attractive to candidates), and to build alignment across the hiring team about what happens next.

Here’s a sort of FAQ for an organization, Interviewer Questions for “Time by Ping” , based on one of those lists of “Questions you should ask when applying for a job”. Some of the questions are fairly pointed! Being willing to answer those questions in a straightforward way, unprompted and publicly, is another way to make your organization stand out from the 3.2 zillion other orgs hiring for technical computing and data roles.

The pushback effects of race, ethnicity, gender, and age in code review - Emerson Murphy-Hill, Ciera Jaspan, Carolyn Egelman, Lan Cheng, Comm ACM 2022

When we’re assessing the technical merits of a code contribution, and by extension assessing letters of reference etc about a candidate’s technical merit, we need to be aware of these effects - non-white, non-male, and older colleagues get significantly higher pushback for PRs, controlling for number of lines changed, readability, and other effects.

Managing Your Manager - Brie Wolfson

Back in #95 we had an article by Roy Rapoport about manager “guard rails”, introducing us to the idea that there are spectra people tend to fall on when they are leading, like “freedom vs guidance” or “caution vs speed”. There’s no intrinsically bad side to either end of those spectra, although they can be better suited for some environments than others (nuclear plant safety equipment manufactures tend to avoid “move quick and break things” sorts of leaders in their technical staff, one supposes). Rapoport’s article talked about the different failure modes for leaders and the far ends of those spectra, and that you should have ways of detecting if your tendencies are causing problems.

In this really nice article, Wolfson gives a deeper typology of managers (but it could also be stakeholders, or even peers) along six dimensions:

She also gives very detailed advice about successful ways of working with people who lean strongly to one side or the other of those spectra. The advice is very actionable and helpful; the article is worth reading in its entirety.

15 Ideas to Build a Kick-ass Developer Ecosystem - kamal laungani

As with people or project management, the key to product management is not brilliant insights or a certain personality type, but just taking the work seriously and doing it diligently and consistently, while keeping some straightforward strategy and goals in mind.

I’ve said that research computing teams can learn a lot from consultants, and product management experts. If your product is largely software-developer related, say libraries, or data resources available over an API, then DevRel (developer relations) teams are also doing work relevant to you.

Some of the points laungani makes that could easily be relevant for a medium-sized software product in research:

An explanation of user stories from the point of view of big scientific software. Probably pretty familiar material to us, but maybe useful as a resource for stakeholders wondering why we want feature requests in a more specific format than just “Make it work better!”.

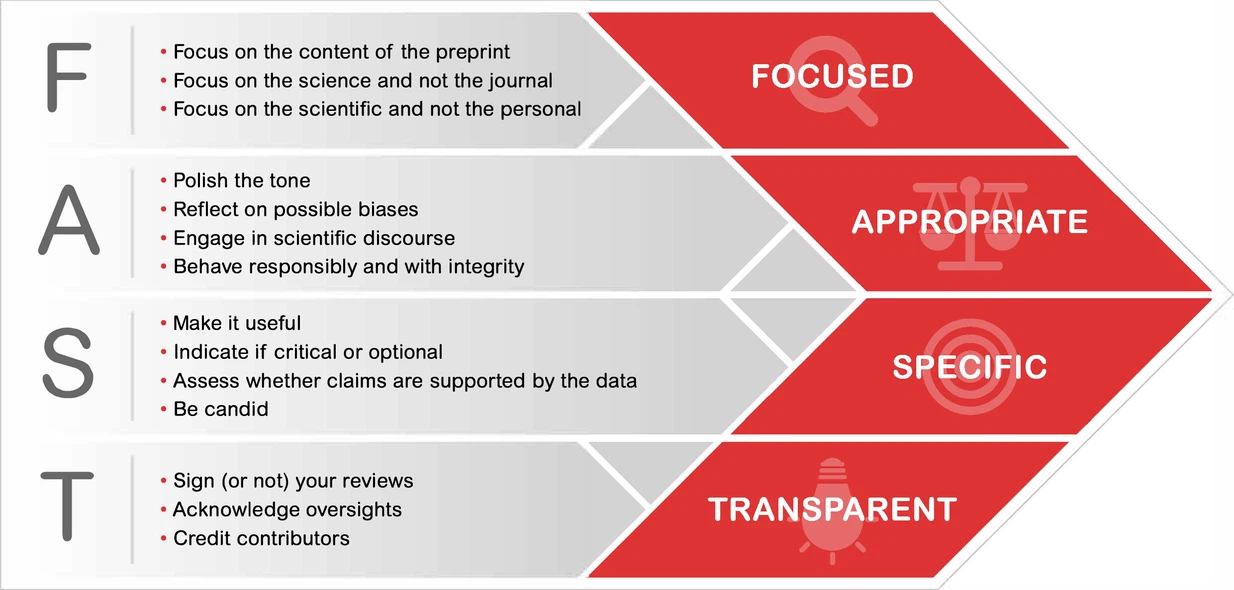

A preprint advocating for improved reviews of papers and especially preprints: Point of View: Promoting constructive feedback on preprints with the FAST principles by Sandra Franco Iborra, Jessica Polka and Iratxe Puebla, in eLife.

Computational Social Science Research Lab Launched in Singapore - HPC Wire

One of the joys of the last decade or two has been watching research computing and data become part of the mainstream, even in fields where it was all but nonexistent.

Here A*STAR and the Singapore Management University announce a S$ 10M joint lab for data-heavy computational social science, “to address people-centric issues in human health and potential, urban solutions and sustainability domains”.

We fixed f-string typos in 69 of the most popular Python repos in only one day. Here’s how. - Higher Tier Systems

Cute story here which ties together several topics of interest to research software developers, like the power of static analysis and the challenges of adopting new features.

Maybe more importantly, an issue we’ve covered from #11 to #100 - low quality error-handling and logging code. One of the reasons that a huge swath of the issues with the repos above hadn’t been seen by developers was because they were lurking in error-handling or logging code. Such code is chronically under-reviewed and under-tested, and which at best can make debugging much more difficult, and at worst can cause failures in the parts of the code that are supposed to help reduce failures.

Interesting story about selling GPL software, in this case a mobile app, where (for GPL compliance) the software is provided through the purchased app, but not generally available on, e.g. GitHub. I don’t think this is the approach the community wants in research software development, at least for methods (data analysis or simulation) where we value transparency, but maybe for more general tooling?

The more usual pay-for-support or pay-for-hosting seems to me a little bit more research computing and data friendly, but it’s good to be open to other approaches.

Good extensive overview of C++ 20 Ranges, and their use with non-modifying algorithms (like search or for_each).

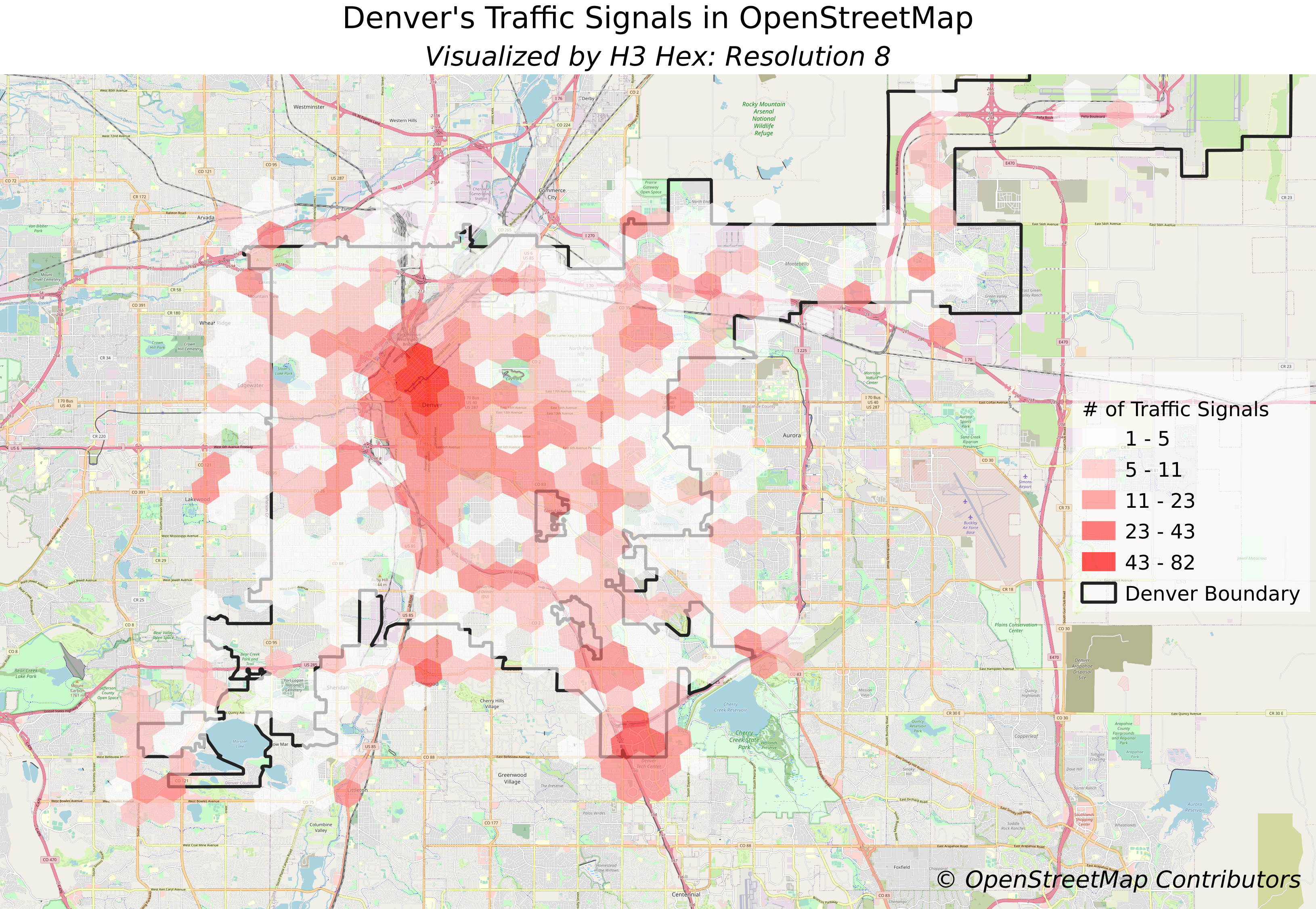

Using Uber’s H3 hex grid in PostGIS - Ryan Lambert

Lambert gives a nice tutorial overview of using a postgres extension, H3, in the PostGIS, a spacial database extender. I’m not GIS-y enough to summarize it in any sensible level of detail, but it’s a really clear walkthrough.

)

)

It’s becoming increasingly clear that data-intensive computing, especially AI, is the current driver for big compute, even for HPE which owns venerable HPC shop Cray. Here’s Next Platform’s take on HPE’s announcement of its own AI stack (software + hardware). Relatedly, here’s HPC Wire’s summary of a talk given by NERSC’s Wahid Bhimji, of “AI for Science - Early Lessons from NERSC’s Perlmutter Supercomputer”.

Richard Pelgrim of Coiled walks us through Common Mistakes to Avoid when Using Dask. I cannot agree enough with this sentiment:

We all love our CSV files. They’ve served us well over the past decades and we are grateful to them for their service…but it’s time to let them go.

Incident management best practices: before the incident - Robert Ross

Incident Analysis 101: Techniques for Sharing Incident Findings - Vanessa Huerta Granda

You’ll know, gentle reader, that I’m a big proponent of learning from incidents, and sharing them with researchers who after all deserve to know why they couldn’t do their work for some period of time. Here’s a pair] of good articles about preparing for an incident, and putting together and sharing the incident report afterwards.

In the first article, Ross talks about clarifying ownership for various services and systems, and clarifying the roles that need to be taken up during an incident. In the US, FEMA has roles for Commander, Mitigator, Planning, and Communication - deciding, doing, figuring out next steps, and communicating internally and externally. All of those tasks need to be done, but for smaller teams managing smaller incidents, one might want to combine those tasks into a smaller number of roles. Then the process - when an incident is called (what’s the threshold?) and what the process is once called needs to be clarified.

With the clarification done, you check your knowledge and for incidents the way you prepare for anything - practicing on dry runs, including with communication.

In the second article, Granda talks about the why’s and how’s of writing up the findings of an after-incident review. The benefits include transparency to users, which helps build trust. But benefits also include clarifying the lessons learned by the team and documenting things so that knowledge can be shared, revisited, and built upon. We’re in the science business - when new things are learned we should write them up and publish them! Granda walks us through the process and even gives us a template.

Making operational work more visible - Lorin Hochstein

In the f-string failure article in software development, I pointed out that log and error handling code was under-reviewed and tested. There’s probably a bigger lesson one can take from that on the undervaluing of supporting or glue or infrastructure work compared to “core” work.

And sure enough, one of the huge downsides of operations work is that when everything goes well, it’s invisible.

Above, Granda walks us through writing up an incident report and sharing it so that users (in our case, researchers) know what’s going on, and so that we build a pool of knowledge internally with the team. Hochstein suggests doing the same, for the same reasons, with incidents that don’t happen, and with routine debugging and improving of performance behind the scene:

Here’s the standing agenda for each issue: Brief recap, How did you figure out what the problem was, How did you resolve it? Anything notable/challenging? (e.g., diagnosing, resolving)

Getting in the habit of writing up and sharing — internally and externally — all the routine but notable work of Operations teams has the same benefits of writing up big incidents. It improves transparency, is generally pretty interesting to a small subset of users, it builds a knowledge base, and it builds trust.

We’ve talked about “diasterpiece theatre” before - testing a system’s resilience by intentionally breaking something and sitting around to watch it play out. Here’s what happened when Dropbox unplugged one of its datacenters to test its disaster recovery.

The writeup on Slack’s big downtime on Feb 22 (my first day on the new job, which was awkward!)

OpenbSSF’s Package Analysis tool for scanning open source packages for malicious behaviour.

Interesting - fine-grained DAG workflows for heterogeneous computing: pathos.

zq, a jq-like tool with a rememberable syntax.

In possibly-related “if your product is hard to use, people won’t want to use it” news: the case against SELinux.

If you’re like me, most of your OS knowledge comes from OSes managing homogenous cores. Here’s a nice read on how MacOS manages M1’s “Performance” and “Efficiency” cores.

Speaking of - the M1 Ultra is well and properly fast on a classic single-node fluid dynamics benchmark.

It’s always possible to clear at least one line in tetris.

Learn more than you expected about PCIe and standards complience as you read one person’s story of trying to get a graphics card plugged externally to a Raspberry Pi.

Remember the Red Book and the Blue Book? The history of postscript.

And that’s it for another week. Let me know what you thought, or if you have anything you’d like to share about the newsletter or management. Just email me or reply to this newsletter if you get it in your inbox.

Have a great weekend, and good luck in the coming week with your research computing team,

Jonathan

Research computing - the intertwined streams of software development, systems, data management and analysis - is much more than technology. It’s teams, it’s communities, it’s product management - it’s people. It’s also one of the most important ways we can be supporting science, scholarship, and R&D today.

So research computing teams are too important to research to be managed poorly. But no one teaches us how to be effective managers and leaders in academia. We have an advantage, though - working in research collaborations have taught us the advanced management skills, but not the basics.

This newsletter focusses on providing new and experienced research computing and data managers the tools they need to be good managers without the stress, and to help their teams achieve great results and grow their careers.

This week’s new-listing highlights are below; the full listing of 134 jobs is, as ever, available on the job board.