This week I did something a bit different: I interviewed Matthew Smith, ARC Research Systems Manager at the University of British Columbia.

We had a great discussion, which touched on the self-doubt that comes with first becoming a manager of experts, working with other teams to have bigger impact than your team can manage by itself, transitioning to remote work as a new manager during the pandemic, the growing need for research platforms, the importance of campus-wide communities of practice, and the coaching mindset to leading a team.

My favourite quote came from the end:

Just love what you do, love the people that you support. I think all of us in research computing are in a unique position. It’s quite the niche that we’re involved in here, and I think we have a rare opportunity to contribute to what I certainly see as one of the key parts of society, which is research, new learnings, new innovation, and being able to support that is a rare opportunity.

I enjoyed this conversation, and I hope you do, too! The transcript and recording can be found here.

One of the comments I get a lot about the newsletter is along the lines of “I’m so glad to hear that it’s not just me wrestling with these problems”. I’m going to continue with these interviews, and we’ll figure out the best ways to share them with the community. Are you interested in being interviewed, or is there anyone you’d like to hear me speaking with? Any topics you’d like to hear covered? Hit reply, or email me at [email protected].

One more thing - The topic I get the most questions about these days is hiring. This is actually a great time to hire, with many private-sector firms freezing their hiring while economic conditions are uncertain.

This newsletter has covered a lot of hiring topics over the past (almost) three years, and I’ve gotten a lot of useful feedback - thank you!

I’d like to distill that material down to a single document that could be as useful to as many people as possible. I’ve started putting everything together into one PDF: so far the table of contents is below.

If you’d be interested in this material, or would send it to someone who would need it, could you go through the table of contents and tell me what you think? Is this what you’d want to read? Are there things missing, or (more likely) things you don’t care about that can be skipped? Would you be willing to leave comments on a first version of the material? I’d appreciate any feedback - just hit “reply” or email me at [email protected]. Otherwise, just skip ahead to the roundup

Background

Avoid Common Meta-Mistakes

The Process

Step 1: Begin with the End in Mind

Step 2: Define the Onboarding Process

Step 3: Define the Evaluation Criteria

Step 4: Define the to Evaluation Process

Step 4: Write Up the Candidate Packet

Step 5: Figure Out Where To Find Candidates

Step 6: Write The Official Job Posting

Step 7: Actively Recruit

Step 8: Running The Hiring Process

Step 9: Running The Onboarding Process

Making Things Easier The Next Time

Build on What You’ve Done

Develop a Bench: Grow Your Team’s Professional Network

Consider An Internship Program

Build your team’s external visibility

Appendices

And now, on to the roundup!

Split Your Overwhelmed Teams - Thomas A. Limoncelli, Operations and Life, ACM Queue

I’ve mentioned before that in other fields, people learn a lot about people systems from case studies. We don’t generally get opportunities for that, so I like to include anything like a case study wherever possible.

Here, we have something of a case study. A service reliability (SRE) team — cross-cutting technical software/operations experts charged with keeping a service up and running both preventatively and in the case of outages — had high attrition and the people were unhappy.

His SRE team was suffering from low morale. People were burning out. Attrition was high. People leaving often cited high stress levels as the reason.

There’s two lessons we can take from this article that are very applicable to our teams.

The first is: If you take smart, driven people who want to help, and make them responsible for an infeasible range of work, they will burn themselves out, even if the workload itself isn’t that bad:

People were stressed because they felt incompetent. Six major areas of responsibility meant that no matter how good you became at one thing, there were other areas that you always felt embarrassingly ignorant about. In simple terms, the team was feeling overwhelmed. […] When I talked with members of the team, I often heard phrases such as “I feel stupid” or “At my last job, I was the expert, but I’ve been here a year and I still don’t know what I’m doing.”

The second is that “not enough funding” or “not enough people” is a problem everyone faces. We tend to think of it as a uniquely academia problem. It’s not. There is no team, in any sector, who couldn’t accomplish more and bigger things, worthwhile things, if they had a bigger budget and larger headcount. But they don’t.

Hiring more people is [one] solution, not a problem. By restating the problem as one of morale and stress [LJD - or too large a scope for the team size], we open the door to many possible solutions.

Not as much funding as you could make effective use of, not as many staff as could be kept busy, isn’t itself a problem. It may well be part of the cause of other, more specific, problems. Focusing on the specific problems increases the range of solutions available. More money or staff might help; another approach is to scope down, focusing one’s effort where one can have the highest impact, and get very very good at that work.

Ten Simple Rules for Running a Summer Research Program - Joseph C. Ayoob, Juan S. Ramírez-Lugo

Slack: How Smart Companies Make the Most of Their Internships - Jessica Wachtel, The New Stack

As you know, from the newsletter (and the hiring ToC!), I’m a huge fan of internship programs. They’re an important mechanism for us to train and develop junior folks and so disseminate knowledge. They also help us improve our hiring and onboarding skills by letting us iterate quickly on them. And they help our team develop a larger professional network, with direct connections to people we wouldn’t otherwise necessarily reach.

Ayoob and Ramírez-Lugo look at starting a summer research program from scratch, in the context of an academic department. But their approach makes just as much sense for technical interns:

Wachtel interviews Eman Hassan at Slack, who sees the same benefits to internship programs as I do; Hassan focuses more tactically on the individual projects for an intern, and sees success requiring:

Delegation - Azarudeen

Delegation is one of the key practices of our job. Like a lot of things, it’s that delegation is hard to do well, but it’s easy to mess up. The author give the four key steps:

And the three most common failure modes:

I’ll just add that delegation is much more like to be successful if you have a practice of one-on-ones with your team member. Those will help you build up that trust, learn what directions they want to grow in, and align these delegated tasks with areas they want to grow. It also requires that you are able to give them effective feedback, to keep nudging them onto the right track in a way that maintains trusts and helps them develop skills.

Reminiscing: the retreat to comforting work - Will Larson

Pairing well with the delegation article above, Larson talks calls out snacking on “comfort work”, retreating from ambiguous and stressful work in our current roles by doing clear and familiar work of the sort we used to do. Maybe ship a little code and close some tickets, or clean up a system image, or “help” with that email to the user community, or analyze some data a few different ways to make just the right figure for that presentation..…

As Larson makes clear with his analogy, a little bit of snacking isn’t necessarily terrible! But it’s a detour from the “nutritious”, real work we’re hired to do. It’s a distraction.

The antidote is to be focussed on what matters:

To catch my own reminiscing, I find I really need to write out my weekly priorities, and look at the ones that keep slipping. Why am I avoiding that work, and is it more important than what I’m doing instead? If a given task slips more than two weeks, then usually I’m avoiding it, and it’s time to figure out where I’m spending time reminiscing.

The benefits of using our Data Safe Haven service - University of Manchester Research IT

Ah! It’s nice to see examples of RCD teams explicitly pitching their solutions in ways that would be compelling to researchers, rather than focussing on the feeds and speeds. This blog post by the Manchester highlights the advantages of their data safe haven service over a “roll your own” approach:

I love this, and would love to see more teams adopt this approach.

You don’t need to have it perfect to start, either. the nice thing about even starting to list advantages like this is that now you have something you can quickly iterate on. In conversations with potential clients, you can see what does and doesn’t resonate, and tweak or reprioritize. Does “quick start-up time” language come across as more compelling than things like “efficiency” to the researcher? Then you can tweak that. Does “solution grows with your project” work better than “scalability”? You can tweak that. Are there other alternatives than DIY that we should include? Can update that. Oh, your funders really care more about efficiency and risk reduction than what the researchers care about? Or human health researchers use different language than social sciences researchers? You can separate the pitch out into versions tuned for each audience. You can start suggesting grant proposal text that is impactful for the funders. etc, etc, etc.

Nonprofit Boards are Weird - Holden Karnofsky

If we have something like a scientific advisory board, we can learn a lot from nonprofits about their interactions with boards.

Like our SABs, nonprofit boards are too often disengaged and uninvolved. Worse, if something bad does happen, they can then leap into action, suddenly getting extremely involved in the nuances of something that they lack important context for.

Karnofsky talks about this phenomenon. He points out that decision-making bodies (or even individuals) can only really be effective if they have:

If one of those links breaks down, then the others often follow.

To re-start engagement, responsibility, and accountability, boards (including SABs) need:

Research Infrastructure Specialist Position Paper - National Research Infrastructure for Australia

This is a great position paper, and one which you might find useful as an advocacy resource for your own teams or organization:

The position of the NCRIS community is that we need to support the development and implementation of a new, simple, and fit-for-purpose classification for RI specialist roles in higher education at all levels, such as by creating a new job family specifically for these roles, separate from academic and administrative job families. This classification system should be based, similar to the current academic scales, on an ability to be promoted without the need for a job reclassification or a substantial change in core duties. The KPIs for promotion should be tailored to the specific responsibilities and development pathways for RI specialists.

They cite some examples, such as career oaths at the Queensland University of Technology (“Research Infrastructure Specialists”) and University of Melbourne (“Academic Specialists”) and some international examples, maybe most interesting is CNRS’s engineer track in France.

I also really like the focus on “Digital Research Infrastructure” holistically. As readers will know, the position of this newsletter is that research software, data analysis, data management, and research computing systems are very much and increasingly intertwined, both in terms of the work itself and the common problems we face. Siloing ourselves into “research software engineering”, “research systems”, “research data management” etc. is deeply unhelpful.

The CommunityRule project by the Media Enterprise Design Lab is a set of template structures for governance and decision making in a community, with examples. So far, it’s pretty sparse, though the plan is to curate a library of contributed rules. Currently it’s a good overview of the very different approaches communities use to structure themselves.

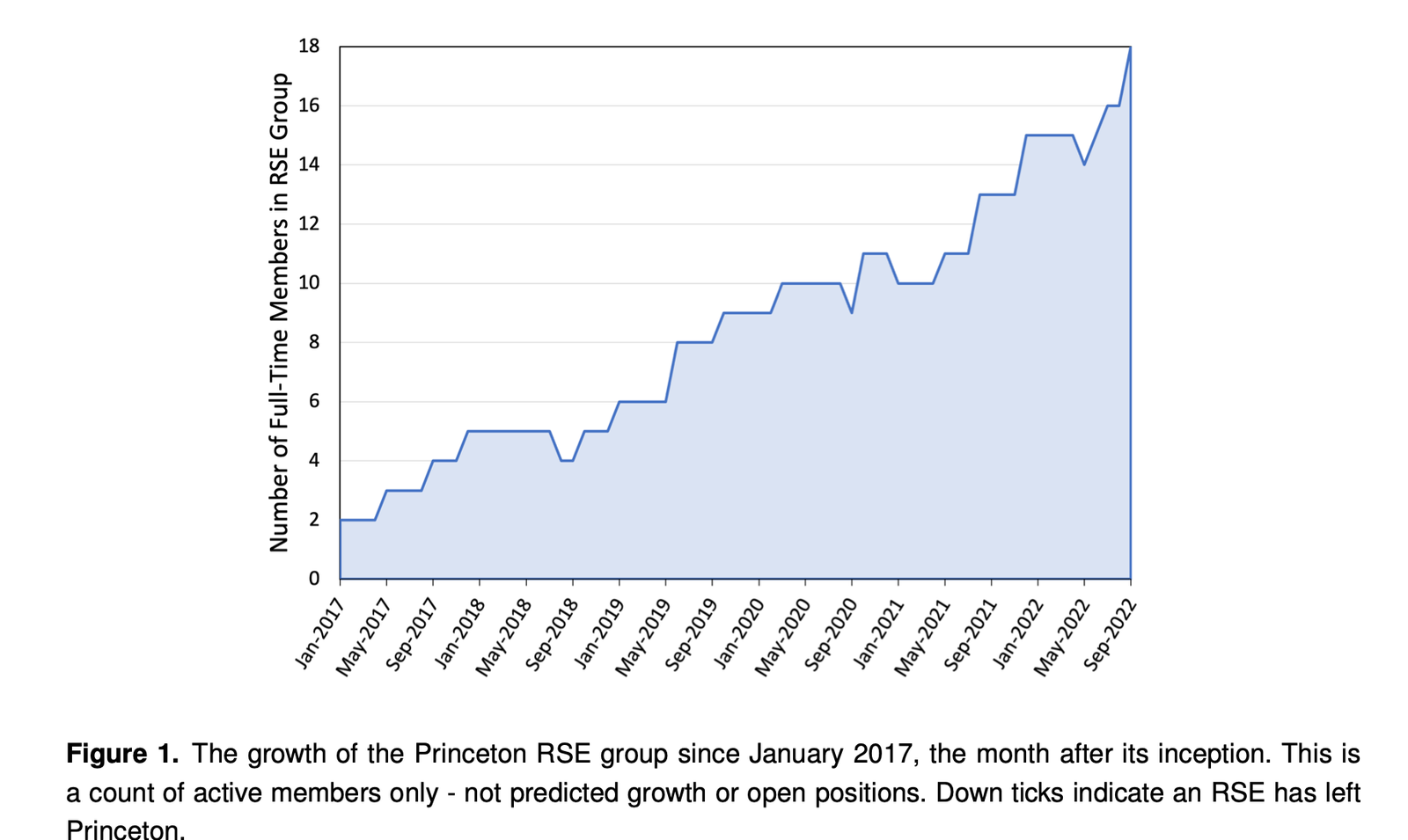

An RSE Group Model: Operational and Organizational Approaches from Princeton University’s Central Research Software Engineering Group - Ian A. Cosden

Cosden dives into the details of Princeton’s central Research Software Engineering group, which was 18 full-time-members at the time of writing.

All team members are both connected to both the central group and a “home department”. They may be Research Computing employees, but co-funded by a partner for 1-3 years and partly embedded there; or they may be completely funded by a parter but still participates in central RSE, connected to that community of practice and “co-supervised” by central RSE so that they can have the technical career mentorship they may or may not have available in the home department. Co-funded positions are competitively allocated as central funding becomes available.

One great thing about Cosden’s RSE group seems to be the clarity of expectations; either way, 85% of the team members time is expected to be on research software projects, as prioritized by the partner department. There are one-on-ones with their RSE manager/co-supervisor, biweekly RSE group meetings, and RSE group events like project sprints, and training (both delivering and learning). There’s a formal RSE Partnership Guide (I’d love to see what that looks like), clarity around performance, publishing, and more.

Fully-funded team members work on projects as directed by the partner (often the team member is hired for a single project). Co-funded team members are generally assigned to a pool of projects that are competitively allocated within the partner project.

We too seldom get to see how different groups operate. Sharing how our teams are organized helps others see the range of options available, even though it doesn’t directly help the person writing it up. As such, it’s an act of generosity, so thanks to Ian Cosden for doing this!

Interesting - GitHub is giving every GitHub user 60 hours/month of (a small environment) on Codespaces, their cloud VSCode environment associated with a repo.

Have any teams started using this sort of approach? It seems like it would be super useful for having a standard dev environment for getting a new developer (or community member) up to speed quickly.

Bioinformatics Core Survey Highlights the Challenges Facing Data Analysis Facilities — Dragon et al, J. Biomolecular Tech.

The question of administrative challenges elicited the most diverse responses, in particular the description of staffing needs and capacity. Responses included concerns about “keeping up with requests,” “burnout with overworked members that need to know a little bit about everything,” “lack of manpower to meet demand,” “needing more bodies,” “hiring good people and making them want to stay and not move to industry,” “too few hands, too much work,” “difficult to get approval for hiring new personnel,” “under-funded and under-staffed,” and general overcommitment and lack of personnel

Azimuth, an open source self-service OpenStack portal for (Linux) VDI, Jupyter notebooks or JupyterHub/DaskHub clusters, k8s clusters, and slurm, looks really interesting.

Schnikies, those new AMD Genoa CPUs look fast.

Latexify.py generates LaTeX math representations of python functions.

Our working conditions can be awkward, sure, but - welcome to brr.fyi, the blog of a lone research IT support staffer in Antarctica.

I’m really enjoying watching a revitalized Fortran community speed-run the buildout of a modern technical ecosystem. FortLS, the Fortran Language Server, has joined the fortran-lang ecosystem.

Speaking of modernity: an upcoming three-day Python for Scientific Computing tutorial… livestreamed on Twitch. Anyone here connected to this, or know of others who have used Twitch for training? Would love to hear more about it.

If this RCD stuff doesn’t work out, maybe we can all become wordle editors.

Syntactically “grep” python code for code patterns you want to change with pyastgrep.

A nice introduction to genomics for software developers.

An embedable graph database that uses datalog as a query language - cozo.

And that’s it for another week. Let me know what you thought, or if you have anything you’d like to share about the newsletter or management. Just email me or reply to this newsletter if you get it in your inbox.

Have a great weekend, and good luck in the coming week with your research computing team,

Jonathan

Research computing - the intertwined streams of software development, systems, data management and analysis - is much more than technology. It’s teams, it’s communities, it’s product management - it’s people. It’s also one of the most important ways we can be supporting science, scholarship, and R&D today.

So research computing teams are too important to research to be managed poorly. But no one teaches us how to be effective managers and leaders in academia. We have an advantage, though - working in research collaborations have taught us the advanced management skills, but not the basics.

This newsletter focusses on providing new and experienced research computing and data managers the tools they need to be good managers without the stress, and to help their teams achieve great results and grow their careers.

This week’s new-listing highlights are below in the email edition; the full listing of 176 jobs is, as ever, available on the job board.