In #153 I mentioned Arm’s new hybrid training delivery model, where they have synchronous meetings for kickoff, Q&A sessions, and closing; but the bulk of the material is pre-recorded and students go through it on their own pace asynchronously. This is a good example of the kind of leverage I was talking about last issue, where the team is aiming to have a similar training impact with a lot less staff time by relying on things they’ve already created (labs, assignments, recordings of previous lectures) and something that already exists (the cohort of students).

A reader wrote in suggesting they were experimenting the same idea:

[…]So I have some comments on the ARM training delivery. In the previous semester, we conducted 2 rounds of our workshop series […] This semester we are more short staffed so only did them once each and only on zoom. All participants said they preferred zoom delivery rather than the nice room […] But we also have recordings on our YouTube channel for asynchronous delivery. We are contemplating just promoting the videos and offering our Office Hours if anyone would like to discuss the content, especially the hands on exercises.

This could be really useful, especially if there’s some kid of forcing function for students to keep going through the material together! I’ll be excited to see how this works. Are there other teams trying similar things? Let me know - just hit reply or email me at jonathan@researchcomputingteams.org.

Last week I talked about the importance of making time to have our biggest impact on research by continuously getting better at what we do, having the same impact with less and less effort.

Once we start doing that and can start imagining some room on our calendars for new work, how do we decide on what new things we should be doing? How do we know what would have the biggest impact?

One common approach that absolutely does not work is sitting alone in our office, or talking with our team, and trying to divine it ourselves. It’s easy to fall into this trap! After all, many of us were researchers at earlier stages of our career, and we know what was and wasn’t valuable to us, then.

But research is wonderfully diverse. Most research problems are not the research problems we were investigating. Most researchers are not us. Even within a field, people have fantastically different needs. The research groups we know best will still surprise us with what they tell us they find valuable and and highest-impact about our work, and what they don’t like. Those further afield are even bigger mysteries.

Yes, readers, I’m afraid it’s true. The only reliable way to find out what matters most to researchers is to ask them.

These conversations can and should be ongoing; it’s good to periodically have a “listening tour” where there’s a flurry of one-on-one or one-to-many conversations, but a conversation once a week with a different researcher along these lines is a useful and grounding practice to have.

In an ideal world, it wouldn’t always be you or someone on your team having these conversations, but someone at one arms-length remove, so that the researchers can be one notch more candid. Your scientific advisory board, if you have one, is a great group of people to be having these conversations. Unfortunately, a lot of us don’t yet have the advantage of having an SAB that productively and valuably contributes to the work of our team. So unless we have someone external we can call on, it comes down to us.

I’ll talk about one-on-one conversations here; if you can get yourself invited to departmental meetings or organizational meetings at research centres or the like, that can be very efficient as well as effective. People are more candid in groups.

Either way, there is one cardinal rule about these kinds of meetings: we are not there to talk about the work of our team and what we do. Honestly, we’re not really there to talk at all, except to ask questions. We’re there to listen.

For research groups we’re already working with, we send an email with a list of questions, saying that we’d like the opportunity to talk with them for 20 minutes or so about these questions, to find out what they like and what we could do to support their research even better. A good starting list of questions looks like:

With each of these questions, ask followups and clarifying questions, and take notes.

Some suggestions:

If you haven’t done these for a while, I promise you that after two or three of these conversations you will have heard something that surprises you. People truly valuing something you never took seriously, or having no use at all for something your team takes great pride in, or a real problem that in the future your team could easily do something about.

Afterwards, write out a summary of your notes, send it with your thanks, and ask for any corrections if you got anything wrong. Writing the summary will probably take as long as the meeting did, maybe longer, but it’s sort of the whole point of the meeting - documenting what you learned in an easily-looked-up form, and showing that you listened.

It’s even more important to talk with researchers who are not clients of ours but who we might expect to be given their work and the services we provide.

I’m going to be a little firm here - far too many of us lie to ourselves about why possible researcher clients don’t use our services. It’s the classic Fundamental Attribution Error. And the more we don’t talk to them about it, the more we can make up convenient stories about why they choose to go it alone or with someone else.

I was at a meeting recently with a number of research systems teams, and the usual stories came up about why researchers don’t use the shared cluster: “they just want to get a grant for hardware so they can list it on their CV”; “too greedy to share”; “don’t care about their postdocs, just want them for cheap sysadmin labour”.

In my day job, I talk with researchers who want to buy compute hardware many times a week. I routinely hear very different stories:

Similarly with the difficulties of hiring; we can make up stories about “candidates just want money these days, they don’t consider any job that pays less than tech”, when the reality is much more nuanced (#147).

We can’t possibly make good decisions about how to impact researchers if we’re making up our own reasons why our services aren’t being taken up by some researchers. It may not even be wrong or bad that our services are good for other researchers but not them! But we can’t make that judgement call in any principled way without knowing the truth of the matter.

The questions we ask of researchers who don’t use our services are mostly the same, and we follow the same approach. Again, we don’t talk about what we do, we don’t try to correct misapprehensions - not during this meeting. If there are valuable things to follow up on, we can extend an offer to a second discussion when we send the meeting notes.

Once we have good initial data, and a mechanism for continually collecting that data, a bunch of things become possible. We can ask for testimonials (which I’ll talk about at some later time); we can start focussing our efforts; we can align our biggest possible impacts with organizational goals, and more.

Resources I like for this:

What do you think? Have you gone on similar “listening tours”? Have you been surprised by what you’ve heard? What are the toughest conversations you’ve had a result? Let me know - hit reply or email me at jonathan@researchcomputingteams.org.

And now, on to the roundup!

Across the way over at Manager, PhD 148 , I talked about task-relevant maturity, and how the “right” amount of oversight was a function of both the task and the person performing the task. There were also articles in the roundup on holding team members accountable with compassion, and coaching the team a a whole and not just individual-by-individual.

Team: Identify the OverHelpers - Rathish Raj

I’ve been this person, and there’s a good chance you’ve been, too. The person who always chips in, is the go-to person for a bunch of things, chimes in while on vacation or works at night, often because they’re quite experienced in some area that the other team members aren’t.

It’s almost always well-meaning, and it’s bad. It hurts the overhelper, it hurts the team’s growth and morale, it introduces bottlenecks, and it has to be gently but firmly curbed. In a lead or manager it’s even more damaging, to ourselves (because the wider scope of our roles means we’ll vastly overwork ourselves) and to the team (who can’t really decline our “help” and learn to do it themselves).

Our team can’t achieve our goals of having as much impact on science as possible if one person holds all the knowledge for some things and becomes a bottleneck, or is the sole person responsible for certain kinds of work. We have to have expectations and processes in place for transfer of knowledge, growing more junior staff, encapsulating knowledge in tools and documents for others to use, etc.

Raj identifies some patterns (especially in software development) to help identify overhelpers, and suggests putting some structures in place to bring others in and stop the overhelpers from constantly contributing. As managers and leads, we can be a bit more directive, and also set clearer expectations about growing junior team members and when it’s appropriate to step back from certain tasks, even if it might not be done as well as if the overhelper had done it.

We all need help learning to delegate and let go some times, and so do our team members. Identifying that is a good starting point, and Raj’s article helps.

Do you or have you had similar problems on your team? How have you handled it? Email me and let me know.

A Framework for Prioritizing Tech Debt - Max Countryman

The 25 Percent Rule for Tackling Technical Debt - John DeWyze

Our teams are technical experts, with high technical standards. And some of the technical stuff we’re working with… does not meet those standards.

And as technical leads or managers we have to decide what if anything to do about that, and how to proceed. We want to make sure we’re directing our teams efforts to things that really matter for scientific impact, and not just making what comes down to aesthetic improvements for our own internal admiration. We’re making tools, not sculptures.

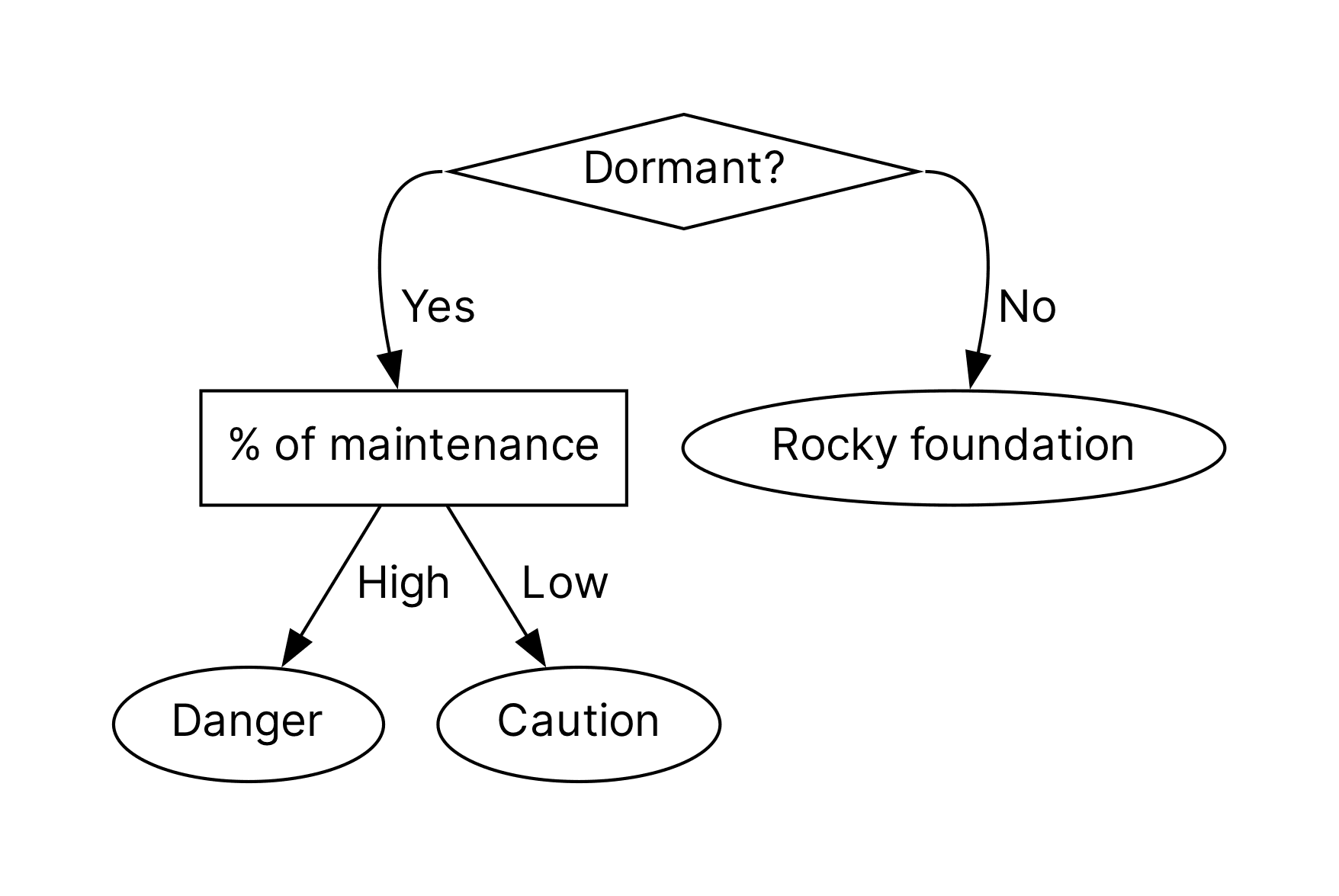

Countryman’s article offers two ways of thinking of deciding whether technical debt needs to be addressed, and if so what is highest priority. First is to baseline the cost to the team of doing nothing:

If we choose to do nothing, will this issue become worse, remain the same, or improve? If it’ll become worse [high interest debt], how quickly will it degrade? If it remains the same [low interest], how much disruption is it causing today? If it’ll improve [zero interest] , at what point will it improve to the degree it’s no longer an obstruction?

And the second is to consider how active work is on this older piece of the system:

DeWyze offers a recipe for how to structure time spent on such work once it’s been identified and prioritized

Tell me about a time documents - Sally Lait

As manager and leads, there’s lots of reasons why taking notes on what you’ve done, what went well, and what went poorly and what you learned from it, is a good thing. It helps you fight managerial sensory deprivation (#117), notice changes (#42) learn what works and what doesn’t, and learn faster.

But there’s another advantage, too. Periodically reviewing what you’ve done and learned over the years as a manager and leader, and making sure you have concise ways of describing those in story form, is fantastic interview prep for behavioural “tell me about a time” questions. What’s more, you end up building a library of stories that will be useful throughout your career, whether for interviewing or for illustrating a point.

You don’t necessarily need to know the questions ahead of time - any one story will generally be useful for demonstrating a number of competencies.

Lait describes these “Tell me about a time” documents. She has a great (and long) list of potential prompts that you could use to start building out your own version of this document. If you don’t have a library of notes yet to start with, you can begin one by thinking up and writing down answers to some of these questions. Reviewing these stories before an interview - and making sure you have a story for every responsibility and skill requirement in the job posting - is a terrific way to make sure when similar questions come up in the interview, you have good answers to hand. It’s less stressful and the followup discussion will be more interesting.

I’ll make one other note - STARL (situation/task/action/result/lessons), SOAR, and the like are great checklists to make sure you included key things, but they can make for stilted templates for many stories. Just write it up in your own words and go back and make sure there’s something there for each letter in whichever acronym you like.

Better incentives are needed to reward academic software development - Merow et al, Nature Ecology & Evolution

It’s great to see more and more communities understanding the importance of research software, and wrestling with the problem of how to support the increasingly urgent maintance and further development of research software. This correspondence has a fairly scathing upstairs/downstairs illustration by Cirenia Arias Baldrich of those who support software downstairs, and those who publish with it upstairs.

The authors succinctly hit a key point here:

Similarly larger grants are available to support new software rather than maintenance.

This is completely true and utterly backward, since it’s the older software that enough people are using to require maintenance that has proved its value to science, and not the yet to be written, hypothetical future software. (Indeed, issue #1 included a fairly strong take by Andreas Müller, “don’t fund software that doesn’t exist”).

Like many such articles, a proposed solution is to count software updates as research outputs. I’m deeply skeptical of this approach, which people have been calling for over decades. The entire value of research software that is actively being used is that it is a powerful research input. The fundamental problem here is that we don’t have reliably good ways of funding research inputs (unless they are paid for by a grant with money going to a vendor, which is an unlikely model for open-source software). It’s this much larger issue that needs to be addressed, rather than hoping that making new versions of software publishable will mean that job security and funding somehow accrue to the product and producer. Researchers on grant and tenure panels or reviewing papers could long since have been granting publications and tenure and funds to research software teams if that’s what they wanted to do.

The Report on the AHRC Digital/Software Requirements Survey - D. Barclay, Software Sustainability Institute

Report on the AHRC Digital/ Software Requirements Survey 2021 - Sufi, Bell & Sichani

This is “a report by the Software Sustainability Institute (www.software.ac.uk) (SSI) on the Arts and Humanities Research Council (UKRI AHRC) community to better understand views on digital/software tools, experience of development of such tools, practices, learning intentions and preferences around how projects involving digital/software should be resourced.”

It’s interesting to read what this community (very different than the one I was trained in) is thinking about for when it comes to research and scholarly software, and most interesting of all is that the needs are very similar.

The report emphasizes the importance of:

And has many excellent recommendations to funders (fund skill development and knowledge transfer; adopt successful schemes from elsewhere), institutions (provide and fund in-ouse expertise, provide training and infrastructure) and nascent communities of practice (establish learning opportunities, seed networking and collaboration, encourage and disseminate good practices, host particular projects)

pandas 2.0 and the Arrow revolution (part I) - Marc Garcia

Pandas 2.0 is going to have an Apache Arrow backend for data. This is going to eventually be a pretty big deal for large or complex data analyses - and not just because it’ll be faster, and has better data-type and missing-value handling. It will mean the in-memory data representation is now compatible (and can be used in place) by a wide range of other tools - databases (duckDB), analysis and plotting tools, file handling tools… Garcia goes much deeper into this.

Intel Announces it is 3 Years Behind AMD and NVIDIA in XPU HPC - Patrick Kennedy

I don’t love this headline. The big news is that, on a Friday, Intel announced that it was killing off Rialto Bridge (which was going to be the successor to the Ponte Vecchio accelerators going into Argonne’s Aurora exascale system), and aiming straight for an “XPU” GPU and CPU on the same package for Falcon Shores. The first version of that in 2025 may or may not have the CPU and GPU fully integrated, but later on it will be.

The reason this seems so big to me is that all of the bigs (AMD, Intel, and — disclaimer — NVIDIA, where I work now) have now fully committed to these XPUs/APUs/superchips/whatever you want to call them - one or more accelerators and CPUs tightly integrated on the same package. This is going to be a huge change for HPC and some AI/ML (especially things like reinforcement learning) workloads, it’s going to unlock some really exciting possibilities, and it’s going to take a few years for us all to really figure out how to program these beasts effectively.

Unfortunately there’s not nothing we can do for the next few months until these systems start to become available, but it’s going to be a really exciting time, and I’m genuinely enthused about this. It’s another step along the path of CPUs Getting Weirder (#51), and I don’t think that path is going to end any time soon.

Something that may be of interest for those supporting users who want to be able to easily stand up web applications - coolify, a self-hosted heroku/netlify kind of service.

The argument that flash is going to kill disk in a way that SSDs never quite managed - told by Timothy Prickett Morgan and Pure Storage over at The Next Platform. A big part of this is power consumption and space, two things that are perennially in short supply in our data centres.

Rounding the corner of the last section of this document, I downshift so that I can move my cursor, then shift into insert mode for the paragraphs of the home stretch - yes, you too can have a BMW shifter that maps to VIM control codes.

More papercraft models of vintage computers..

Gotchas of tmux and environment variables, a situation that’s tricky and I admit I’ve never once thought about.

“Well, git branches are just references…” yes, but no.

A lot of our teams produce long-form videos. It’s getting easier to make nice quick sharable shorts from them! Vidyo.ai, which has a free tier, will create some for you automatically, and the mobile YouTube app will help you create YouTube shorts from your existing videos.

Another cute tool - copy source code into Slides Source Code Highlighter and it will generate nicely formatted text for you suitable for slides or documents without you having to use a screenshot. Cute!

Implementing and variations on manager support groups. Would something like that be interesting for our community?

Efficient geo-indexing scheme for timezone lookups.

Which may have to be updated, actually, if the Moon gets its own timeezone.

And that’s it for another week. Let me know what you thought, or if you have anything you’d like to share about the newsletter or management. Just email me or reply to this newsletter if you get it in your inbox.

Have a great weekend, and good luck in the coming week with your research computing team,

Jonathan

Research computing - the intertwined streams of software development, systems, data management and analysis - is much more than technology. It’s teams, it’s communities, it’s product management - it’s people. It’s also one of the most important ways we can be supporting science, scholarship, and R&D today.

So research computing teams are too important to research to be managed poorly. But no one teaches us how to be effective managers and leaders in academia. We have an advantage, though - working in research collaborations have taught us the advanced management skills, but not the basics.

This newsletter focusses on providing new and experienced research computing and data managers the tools they need to be good managers without the stress, and to help their teams achieve great results and grow their careers.

This week’s new-listing highlights are below in the email edition; the full listing of 171 jobs is, as ever, available on the job board.