Nurture your best clients first. Plus: Write and get feedback on tech specs; technical documentation guidebook; wrap up projects; talent leaks out of funding gaps; reproducibility of jupyter notebooks; 10 simple rules to manage lab data; NIST on HPC security

For the next few issues, I’m going to talk about our teams as businesses, because viewing our organizations this way is sorely needed and yet hardly ever talked about.

Now yes, every so often I attend a talk of some sort titled “The Business of Research [Computing/Core Facilities/Software Development/Data Science]”. And every single time I do, I hope to hear about:

And every time, what I hear instead is a discussion of the funding compliance rules for the relevant jurisdiction, what money can and can’t be spent on, and some suggestions about how to structure things to meet those requirements.

Now, I get why that is. The rules are incredibly baroque, pretty onerous, non-compliance can have huge consequences, and yet our staff need regular paycheques. It’s a lot to deal with and has to be done. (I actually have a draft in here somewhere of an essay about how the structure, rules, and regulations around our funding, even more so than the amount, hurts science by handcuffing teams in their offerings, forcing them to support science in sub-optimal ways. That’s for another day.)

While not breaking any laws is certainly a necessary starting point, we can and should aspire to greater things than merely “spends money in a way compliant with local regulations”.

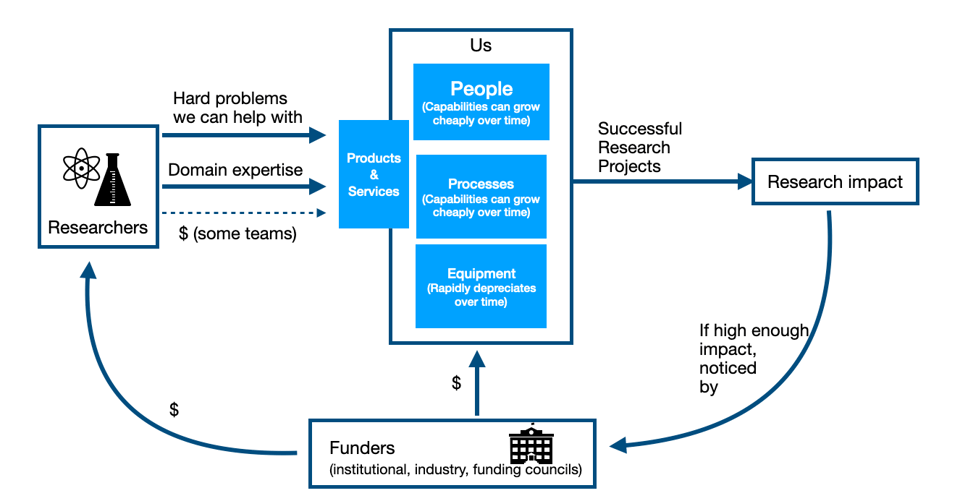

There’s a basic feedback loop, which we want to turn into a flywheel (#44), which keeps our team funded: we provide products and services for researchers, combining our expertise with there’s to produce research impact, which funders adjudicate and then fund us and researchers.

Our teams’ goals are to advance research and scholarship in our communities and institutions as far as we can, given the constraints we face. To do that, we want to focus our efforts on generating as much research impact as possible.

There’s a lot of ways we can do this. Some of them take a lot of time and effort - structuring ourselves around value-add professional services, rather than simply being a cost-centre utility (#127 - tl;dr, cost centres get outsourced).

But if you’re just getting started thinking about how to increase impact, the highest reward-to-effort starting point in almost any sector is: start talking with your best clients more, and invest time in nurturing that relationship.

As leaders of service teams, we tend to be preoccupied by the communities (or even individual researchers) that we aren’t helping, that aren’t using our products and services for some reason. The fools! Don’t they know how great we are? Maybe if we taught their grad students more training courses….

Sure, growth can eventually happen there, and it’s worth thinking about at some point, but right now they aren’t using your team for some perfectly good reason. Investing more effort into courting them while not changing anything the team is doing isn’t going to be the best first-choice use of your time and effort.

Instead, it’s almost certainly more useful to spend more time with your best clients first.

Who are your best clients?

You might already have an initial sense of who they are. When I talk to people who are unsure, I encourage them to consider which groups they work with who:

These are groups and individuals who are already successful with you, so that they understand the value of what your team provides, in a detailed and nuanced way, from a different perspective than yours. You can:

There’s three reasons to focus on these groups first.

They are already doing high-impact work with you. Our teams’ purpose is to have as much research impact as possible. Doing more work like you’re doing with them will almost automatically mean you are advancing more high-impact work.

Their high-impact work is supported by you, so you and they share an immediate and common interest in making sure your team has what it needs to do its job. They can advocate for you.

Their advocacy to decision makers, or their word of mouth to other researchers doing related work, will be 10x more effective than anything you can say (even if you’re the one giving them the words / bullet points / slides to say it!). Everyone proclaims their own team to be amazing and essential; people tune it out. If a successful researcher says your team is amazing and essential, people will pay attention.

So if your team has the capacity to be doing a little more, my first recommendation is always to start prioritizing current best clients and nurturing a relationship with them. Schedule a chat with them. Ask them some of the questions from #158. Try to set up some regular call (monthly or so) between someone in your team and them or someone senior in their group to make sure everything’s going slowly. Find out other ways you can work with the group.

We tend to focus too much on weaknesses of our offerings, or areas where we have little uptake. Yes, that stuff matters. But unless you’re explicitly being directed otherwise, first build on your teams’ strengths. Take the working relationships that are going really well and invest time and energy into them. Developing those clients is by far the highest bang-for-buck area to start with. Only after deepening and growing those connections should you start thinking about investing effort elsewhere.

What have you found that works and doesn’t work when it comes to developing client relationships with research groups? Let me know - email

jonathan@researchcomputingteams.org

And now, on to the post-long-weekend roundup!

Over at Manager, Ph.D. in issue #168, I laid out the argument I made in my USRSE2021 talk - that people with PhDs (or other experience working in scientific collaborations) already have the advanced management skills they need to be great managers, they just need help shoring up the basic management skills we never saw modelled for us in the academy.

Also covered in the roundup:

How to Write Great Tech Specs - Nicola Ballota

Getting better feedback on your work - James Cook

One of the roles of a technical lead is to make sure problems are well posed, and often that involves writing a tech spec. Ballota gives good advice on writing technical specifications.

One key thing to writing tech specs that Ballota doesn’t cover is that it’s not a one-and-done process, a good tech spec is iterative, and you get feedback from the team (and stakeholders) at different stages.

I like Cook’s approach to making sure you’re getting the right level of feedback at the right stage. Early on you’re looking for big-picture feedback: is this even the right problem, does the approach outlined make sense? Cook calls this “30% feedback”, since the document is only ~30% of the way to completion. Later on you’re looking for more fine-grained feedback - is that diagram clear, are these requirements detailed enough. Cook calls that “90% feedback”.

I like to not only make it explicit how fully-baked something is, but to make the document look like a rough draft when it is in its early stages - hand-drawn diagrams, bullet points, unformatted text. My experience is that people are much more comfortable raising big questions when the thing you’re showing them doesn’t look like a finished document.

Software Technical Writing: A Guidebook - James G

We know that most of our products are pretty under-documented.

The author James wrote a series of blog posts “Advent of Technical Writing” in December, and has now refactored those into a coherent book (epub, PDF) laying out a way of thinking of technical writing broadly, suggested stylistic approaches for different types of documents, and going from a bullet-pointed outline to a full document. James titles the book “Software Technical Writing” but this applies equally to research computing systems, data science or bioinformatics workflows, etc.

It’s quite good and given the way it’s written it could easily be customized or added to for particular locales and products into a local standards guide.

Maybe relatedly, Google Season of Docs, the sibling of Summer of Code, is now open - organization applications are due 2 April. This could help a lot of products out there, and if your team knows it needs to improve its documentation you could get things started with this guidebook, identify specific gaps, and have a concrete project written up in a few weeks.

The Consulting Project Wrap-Up Checklist - David A. Fields

Sort of related to the lead essay this week about nurturing relationships, I’ve commonly teams where projects we’re doing with a researcher just sort of fizzle out at the end. “Ok, we’re finished - let me know if you have any problems!”

That’s a missed opportunity. Researchers are celebratory at the end of a project, looking to get the paper out and already thinking about the next project. This is a great time to follow up with them! Close out the project with some celebratory note, ask for a retrospective and how it went, ask for a testimonial or to write up a success story, ask about what they’ll be working on next and if there are things the team can do to help with them.

Beginnings are auspicious times, but so are endings. Take advantage of a shared success and ask to build on it.

The Value of Stability in Scientific Funding, and Why We Need Better Data - Stuart Buck

Scientific Talent Leaks Out of Funding Gaps - Wei Yang Tham et al, arXiv:2402.07235

Buck writes about the tour de force paper by Wei Yang Tham et al. They linked data from NIH ExPORTER, UMETRICS (University administrative data on grant transactions), and US Census Bureau tax and unemployment insurance records. With that they looked at a natural experiment of sorts - what happened to the people employed in labs where a funding interruption (caused for instance by the US federal government not passing funding resolutions, delaying otherwise successful grant renewals).

That might seem like an edge case, but a shocking ~20% of R01s renewed in FY2005-2018 had at least a 30 day interruption, with a median length of 88 days.

Personnel in those interrupted labs that had been funded by a single R01 had a 40% (or 3 percentage point) increase in likelihood of becoming unemployed - and they were mainly grad students and postdocs. You might think that they preferentially went off and got great jobs in industry, but when the unemployment is sudden and unplanned for it doesn’t work that way; those that did leave employment when the lab was interrupted eventually found employment at 20% less salary on average, and typically aren’t publishing.

This situation affects our own teams, too. Our funding is notoriously uncertain, and if anything I’d imagine we lose even more people when there are funding interruptions - not least of which because when we have them it’s going to be a lot longer than 30 days.

There’s not much we can do here, but we can be aware of it, and this paper might be a useful starting point for discussions with funders when we talk about the effects of funding uncertainties.

Computational reproducibility of Jupyter notebooks from biomedical publications - Sheeba Samuel & Daniel Mietchen

This is a fun paper, which required a really impressive automated pipeline to do, and I think people are drawing the wrong conclusions from it.

Out of 27,271 Jupyter notebooks from 2,660 GitHub repositories associated with 3,467 publications, 22,578 notebooks were written in Python, including 15,817 that had their dependencies declared in standard requirement files and that we attempted to rerun automatically. For 10,388 of these, all declared dependencies could be installed successfully, and we reran them to assess reproducibility. Of these, 1,203 notebooks ran through without any errors, including 879 that produced results identical to those reported in the original notebook and 324 for which our results differed from the originally reported ones.

This is pretty cool! Over 22.5k notebooks from almost 3.5k papers were tested, to which, well, hats off. Super cool work.

There’s a lot of focus in discussions of this work on the fact that 22.5k notebooks, only 1.2k ran. I don’t think that’s anything like the biggest problem uncovered here.

For a one-off research paper, the purpose of publishing a notebook is not so that someone else can click “run all cells” and get the answer out. That’s a nice-to-have. It means that researchers that choose to follow up have an already-working starting point, which is awesome, but that’s an efficiency win for a specific group of people, not a win for scientific reproducibility as a whole.

There are people saying that we should have higher standards and groups who publish notebooks should put more people time into making sure the notebooks reliably run on different installs/systems/etc. That’s a mistake. For the purposes of advancing science, every person-hour that would go into doing the work of testing deployments of notebooks on a variety of systems would be better spent improving the papers’ methods section, code documentation, and making sure everything is listed in the requirements.txt, and then going on to the next project.

The primary purpose of publishing code is as a form of documentation, so that other researchers can independently reproduce the work if needed. But we know for a fact that most code lives a short, lonely existence (#11). Most published research software stops being updated very quickly (#172) because the field doesn’t need it. And trying to reimplement 255 machine learning papers showed that a clearly written paper and responsive authors were much more significant factors for independent replication than published source code (#12). If others are really interested in getting the notebook to run again, then presumably the problems will get fixed up, and the problems will be resolved. The fraction of those notebooks that will be seriously revisited, however, is tiny.

To me, the fact that 6,761 notebooks didn’t declare their dependencies is a problem because it represents insufficient documentation. That 324 notebooks ran and gave the wrong answers is a real problem, because it means there was some state somewhere which wasn’t fixed (again, an issue of documentation). That 5,429 notebooks couldn’t still have all the software installed isn’t, to me, a problem much worth fixing, nor is (necessarily) that 9,1815 notebooks installed everything but didn’t run successfully (depends on why).

Less controversially, this has been out for a while but I hadn’t noticed - Polyhedron’s plusFORT v8 is free for educational and academic research. It’s a very nice refactoring & analysis tool that even works well with pre-Fortran90 code. Most tools like VSCode or Eclipse shrug their shoulders and give up older or non-F90 Fortran code, even though that’s the stuff that generally needs the most work. If you try this, share with the community how well it works.

The value of using open-source software broadly is something like $8.8 trillion, but would “only” cost something like $4.15 billion to recreate if it didn’t exist, according to an interesting paper. That 2000x notional return on notional investment suggests the incredible leverage of open source software. Also, only 5% of projects/developers produce 95% of that value, something that would likely be seen in research software as well.

Ten simple rules for managing laboratory information - Berezin et al PLOS Comp Bio

This “ten simple rules” article is a thoughtful overview of data management in the context of biological sciences experimental data. But they’ve tied their high-level rules to the scientific process in general, not any particular experimental modality, and so the higher level rules (even if not always each of the individual suggestions within the rules) are valuable widely to any data-based scientific explorations.

It’s a nice short well-structured paper chock full of hard-won recommendations, definitely worth a read.

NISP SP 800-223: High-Performance Computing Security: Architecture, Threat Analysis, and Security Posture (final) - Yang Guo et al

The draft version of this document came out a year ago (#155); the final version is a little more nuanced and more explicitly spells out the tradeoffs between security and performance.

I personally find that tradeoff space interesting, and I think the days are waning where we can safely assume that the operator of every HPC cluster necessarily wants to peg the needle to max performance at the expense of flexibility and security considerations. Having the tradeoffs clearly spelled out is helpful in that regard, as is the process of getting everyone on the same page of different “zones” of a large computing system and their specific threats.

It looks like thanks to a new policy by the Linux Kernel team, CVE numbers are going to get weird.

codeapi for browser code playground with visualizations - and an example as interactive release notes for SQLite 3.45. (Have to admit that making release notes interactive would be a fantastic use case for something that lets you noodle around with new features).

Profila, a profiler for numba code.

Numpy 2 will break some stuff.

There’s a new configuration tool, a programming language called pkl. Surely this new configuration language will be the one that finally solves everything.

A deep dive into linux kernel core dumps.

Sometimes we overthink things. How Levels.fyi scaled to millions of users using Google Sheets as a back end.

NASA open-sourced F’, one of their frameworks for flight software on embeded systems.

The director of “Toy Story” is the one who drew the original BSD Daemon logo.

Turn most containers into WASM you can run in the browser with container2wasm.

Subset fonts to only those needed with for your website’s text with fontimize.

Another slice-and-dice CSVs utility - qsv.

And that’s it for another week. Let me know what you thought, or if you have anything you’d like to share about the newsletter or management. Just email me or reply to this newsletter if you get it in your inbox.

Have a great day, and good luck in the coming two weeks with your research computing team,

Jonathan

About This Newsletter

Research computing - the intertwined streams of software development, systems, data management and analysis - is much more than technology. It’s teams, it’s communities, it’s product management - it’s people. It’s also one of the most important ways we can be supporting science, scholarship, and R&D today.

So research computing teams are too important to research to be managed poorly. But no one teaches us how to be effective managers and leaders in academia. We have an advantage, though - working in research collaborations have taught us the advanced management skills, but not the basics.

This newsletter focusses on providing new and experienced research computing and data managers the tools they need to be good managers without the stress, and to help their teams achieve great results and grow their careers.

This week’s new-listing highlights are below in the email edition; the full listing of 54 jobs is, once again, available on the job board.