Offer services worth paying for. Plus: Effective vendor relationships; Teaching Humanists Changed How This Team Teaches Everyone; Service sludge toolkit; Existing knowledge and collaborations improves agility

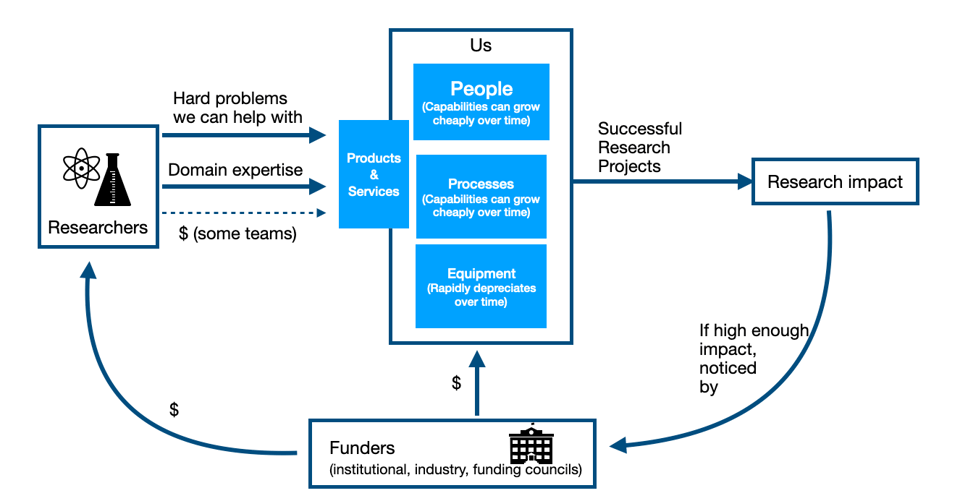

I want to keep talking about this diagram, and point out something that seems logical to the point of inevitability yet which is in my experience pretty controversial for those not operating fee-for-service teams.

In #176, I focussed on the left hand side of the diagram, that the easiest and most effective way to bring in good work for your group is to talk with your best clients (past and present) and see if there were new or more or larger projects you could do together.

In #177, last issue, I talked about the right hand part of the diagram, the importance of having as high a research impact as possible given your teams constraints.

This issue, I’m going to talk about the path from the left to the right, connecting the researcher, costs, and impact. And in doing so I’m going to share what is by far my least popular technical research support opinion. That is: regardless of the actual funding mechanism of your group, if researchers wouldn’t even in principle be willing to pay the full cost of a service out of their own research grants, then we almost certainly shouldn’t offer that service and should do something else instead.

Oh, that’s not controversial enough? Alright, let’s try this corollary: one example of breaking this rule is that many (many) institutions over-provide batch HPC services at the expense of other services that would be more highly valued.

It seems obvious almost to the point of being condescending to point out that researchers know what their research needs.

But the fact is, at the level of which we interact with researchers every day, sometimes we forget.

They quite often don’t know how to do something with computing, or how much effort is involved in getting ABC to work, or which of several kinds of methods to use.

But they very definitely know what they want to accomplish, and what kinds of resources they’re willing to expend to accomplish it.

Demand for free things will always be off the charts. If you have a departmental ice cream social on a hot summer’s day, you’re going to go through every bit of ice cream that you buy for your “free ice cream” stand.

High utilization of that ice cream stand is not evidence for the proposition that providing even more free ice cream is the most valuable use to which you could put scarce departmental resources. It’s not even evidence that it’s in the top 10, or should be a priority at all.

People just like free ice cream.

Researchers are resourceful. If something is available for free, and they can find a way to use that free thing to advance some part of their research portfolio, they will absolutely make use of it. That could be computing, support, software development, data analysis, management, grant-writing support, machine-room time, or what have you.

It’s only when you ask them if they’d write the costs into their next grant that you’ll find out how much they actually value it.

For our purposes, research is infinite. Any individual researcher has countless projects they could take on to advance their research programme, and they can and do pivot that programme and switch their research focus when new opportunities arise.

Research funding, and research support funding, on the other hand, is exceedingly finite.

So every researcher who writes grants is constantly assessing what is the best way they could have their desired research impact, and very critically assessing what is the least resource-intensive way to have that impact. And they are VERY willing to shift the projects they tackle if they see higher bang for research funding buck in a new direction.

Whatever our teams’ source of funding, it comes from that same, super finite, research funding ecosystem as do the researchers’ grants.

And typically, for better or worse, we have a lot of discretion about the exact kinds of activities we perform and services we provide.

As I said in #177, we have a duty to use these funds to perform tasks where they can have the highest impact. And (#173) by that I don’t mean “do something that has non-zero usefulness”. Institutionally, the trade-off isn’t “is doing this better than putting the money in a pile and setting it on fire”. The trade-off is: “is providing this portfolio of services better than disbanding the team and giving the money that would have funded it back directly to highly productive researchers”.

Because if it isn’t then continued funding of our centre is, objectively, hurting research.

That sounds terrible! But:

Our teams not only should have so much impact that researchers would in principle be willing to write our services into their grants, we can.

We know it’s possible, because there are lots of teams, many in our own institutions, which operate this way.

But besides that: consider how hard it is to hire for our teams. Now consider dozens or hundreds of individual researchers trying to hire for our level of expertise and knowledge, probably looking for only part-time or term-limited work.

We offer extremely in-demand experts an opportunity to have high scientific impact by bouncing between exciting projects if that’s what they prefer, or focusing deeply into one area if they prefer that. It’s still hard to hire, but that’s largely because hiring experts like ours is hard everywhere.

Our teams are professional services firms (#127). We bring expertise to bear on challenging projects. More, it’s our team’s full-time job to do so, and we develop skills and produces and processes and automations and knowledge transfer around exactly that.

If we can’t do our work so much more effectively than individual research groups can that they’d happily write us into funding opportunities, then what exactly are we doing here?

I want to point out that I’m not arguing that all technical research support should be fee-for-service. Some should (and probably more than currently is), but there are excellent administrative and equity reasons why particular services are best funded in part or in whole by central funding, just as some of our public services are funded through general taxation while others are supported through user fees.

But the rule we measure ourselves against should still be: would providing this service be, in principle, something researchers would be happy to write into their grants.

I’m describing a way of assessing the research impact per unit research funding investment of a particular technical research support intervention - and in fact, thinking of it the way a researcher would.

There are very specific reasons why an institution might choose to invest in some area of research support even when individual researchers would overwhelmingly argue that the money should be spent somewhere else.

Changing behaviours - sometimes the institution sees a need to change behaviours of how research is done in the institution, and is willing to spend money to make that behaviour change. Some examples:

The thing about changing behaviours, though, is that if successful, at some point the behaviours have changed. Institutions can’t and probably shouldn’t commit to (say) subsidizing good research data management practices from now until the heat death of the Universe. Eventually this should be just part of how research is done (and funded), and the necessary costs should be baked into research grants. Similarly, at some point the desired interdepartmental collaborations will be either be (a) strong and not need the same level of external subsidization, or (b) clearly not happening and should be abandoned.

Developing new capabilities - there are lots of kinds of research support that just can’t be purchased piecemeal by individual investigators on their own. Maybe the institution and some key group of researchers has decided (say) that it’s important to develop strong quantum computing and quantum materials depth of expertise, and some large capital expenditure will be a useful way to spend a lot of money even if most researchers at the institution will not directly benefit.

This is related to “changing behaviour” but the reason for it is different — the big (and presumably one-time) capital purchase is just too large for any one researcher or group of researchers to manage, but the institution putting its muscle behind it one way or another can make it possible.

Again, though — if successful, this new capability then exists. If after some initial experience with the new capability it becomes unsustainable, because not enough researchers feel maintaining and sustaining the capability is the best use of their research funding, then why exactly should it be maintained and sustained?

Lots of teams do have a lot of their work funded at least partly fee-for-service, in which case everything I’ve said will be pretty obvious.

But for the majority of our teams, those that rely in whole or in part from some source of external subsidy, it is important to view our offerings through the battle-weary perspective of our colleagues that do operate purely fee-for-service offerings, or through the perspective of the researchers who have to decide how their own research funds get spent.

“Is this the best use we can put our funding to” is a broad, fuzzy question. “Would researchers be willing in principle to write the full cost of this into their grants” is bracingly concrete.

And teams that assess their offerings against that very high bar are going to be teams whose teams more consistently get to experience having really high research impact in their work. Our team members, and our researchers, deserve that.

One that note, on to the roundup! A short one this week, since the essay went long.

Over at Manager, Ph.D., I talked last week about how the imposter syndrome of switching fields is a lot like that of becoming a manager, and how the same approaches can help.

In the roundup, there were articles on:

Three Keys to Building Effective Vendor Relationships - Scott Hanton, Lab Manager

I want to do a whole thing on this at some point - in my experience, most of our teams do not take anything like full of the relationships we have with vendors. [Full disclosure: I work for a vendor now. But then, I’d argue, so do you (#123)].

The vendors we interact with, whether hardware, software, or services, have a range of deep expertise, and visibility into what a lot of other teams are doing. The individuals, especially the technical ones, are typically interacting with university research support teams (compared to all of the other frankly far more profitable customers they could be working with) because they genuinely value research; and all of the individuals know the importance of mutually beneficial long-term relationships.

All that is to say, these relationships and interactions do not need to be purely transactional. The experts on the vendors’ teams are generally quite open to the possibility of other kinds of collaboration than just waiting for you to place an order.

Hanton encourages us to:

In general, we should try to forge collaborative relationships with experts in our space wherever we find them - under whatever org in our institutions, and even across sectors. And vendors who aren’t interested in having their technical experts have ongoing conversations with you? Well, there’s lots of other vendors out there.

Teaching Technical Topics Effectively: How Teaching Humanists Has Changed How We Teach Everyone - L. Vermeyden and G. Fishbein

This is an interesting paper from last year that I’ve only seen recently, describing how teaching research software & computing concepts to digital humanists made the authors’ training team rethink some aspects of their teaching which improved teaching for everyone.

This was a really interesting read, but hard to summarize - I’ll encourge you to read it if you find the topic interesting.

Sludge Toolkit - New South Wales Governement

I’ve been following the recent rise of digital services in government quite closely; after a lot of very hit-and-miss efforts, there seems to be a growing realization (at least in the anglosphere) that service design requires big picture thinking and attention to detail simultaneously.

In particular, there’s a lot more attention being given to unnecessary friction - or sludge - in the process.

I’ve seen this sort of thinking once or twice in technical research support (e.g. #147, Karamanis’ article “How to redesign a scientific website in three simple steps with limited budget and time”), but not really often enough.

NSW has a “sludge audit” process described, for going through the user-facing pieces of service, identifying unnecessary frictions, and prioritizing their removal.

Effects of prior knowledge and collaborations on R&D performance in times of urgency: the case of COVID-19 vaccine development - Laufs, Melnychuk & Schultz, R&D Management

We investigate how organizations’ prior collaboration and existing knowledge not only helped them cope with the crisis but also affected the vaccine’s development performance. […]. The results reveal that under urgency, organizations with prior scientific collaborations and technological knowledge exhibit a higher R&D performance. Furthermore, a broad network of diverse collaborators strengthened this relationship, thereby calling for more interdisciplinary R&D activities.

I think this article is interesting, for two reasons.

First, it points out how having a network of existing collaborations (whether that’s with other teams within the institution, or further afield) helps groups be more nimble when they need to be, as there’s a network of pre-existing relationships to draw on.

Second, my own interpretation: our teams not only have very broad technical knowledge, but a particularly broad set of existing collaborations, both with researchers and other support teams (or we should). That makes us a potentially vital hub for our research communities when they need to be agile with some uncertainty.

Either way, I think this a pretty good motivation to not only make a point of broadening and “keeping warm” our internal and external collaborative relationships, but to be explicit that our network of relationships and breadth of expertise are important resources we bring to our institutions.

This is a nice primer on “differentiable programming”, a way of approaching programming to take maximal advantage of all the differentiability and continuous optimization tools there are out there now because of AI.

A chess engine in PostScript, for some reason.

Variable colour fonts, for some reason.

I have a soft spot for the Chapel programming language, although interest seems to have stalled out - anyway, Chapel 2.0 is out.

Lots of good Python tracing/profiling stuff out lately, some related, some not: an article from JetBrains on the new-ish monitoring API, profiling Numba code, trace your Django app inside VSCode.

The most efficient way to tell odd integers from even integers, if you’re committed to doing that with 4 billion if statements.

For actual useful optimizations, designing a SIMD algorithm from scratch.

As servers serving single applications (or infrastructure components) become increasingly a typical use case, we’re going to see more custom OSes like this - a database specific OS, DBOS.

You’ve almost certainly seen this already, but just in case - you can link your ORCID ID to your github account now.

I’m sort of surprised I can’t remember an article on this topic before - what impact does floating point precision have on the Mandelbrot set?

And that’s it for another week. If any of the above was interesting or helpful, feel free to share it wherever you think it’d be useful! And let me know what you thought, or if you have anything you’d like to share about the newsletter or stewarding and leading our teams. Just email me, or reply to this newsletter if you get it in your inbox.

Have a great weekend, and good luck in the coming week with your research computing team,

Jonathan

About This Newsletter

Research computing - the intertwined streams of software development, systems, data management and analysis - is much more than technology. It’s teams, it’s communities, it’s product management - it’s people. It’s also one of the most important ways we can be supporting science, scholarship, and R&D today.

So research computing teams are too important to research to be managed poorly. But no one teaches us how to be effective managers and leaders in academia. We have an advantage, though - working in research collaborations have taught us the advanced management skills, but not the basics.

This newsletter focusses on providing new and experienced research computing and data managers the tools they need to be good managers without the stress, and to help their teams achieve great results and grow their careers.

This week’s new-listing highlights are below in the email edition; the full listing of 102 jobs is, as ever, available on the job board.