So, yeah.

Here in Canada, we imposed a sudden and blunt cap on international students - college programs are closing down left and right, and even big research institutions are probably going to see ~5-8% drops in income (Canadian colleagues, if you’re not subscribed to the HESA blog, fix that immediately.) The UK is feeling the bite of Brexit and related on international student admissions so that even Russell Group institutions are cutting programs. Australian University funding has a lot of things going on which I frankly can’t even keep track of.

It’s not awesome that our institutions have been put in a position (with varying degrees of eagerness) of so much reliance on international student fees to balance books, but there it is.

We’re seeing big cuts as a result in because our institutions’ expenses are mostly salaries. What’s more, those salaries are contractually obligated to increase over time (which is good). So minor drops in revenue - even revenue not going up by as much as the mandatory cost of living/seniority increases in salary - has to result in cuts of jobs.

Those revenue drops will touch our research parts of the organization too. It’s frankly not great that the research part of our institutional missions are funded to the extent they are by cross-subsidy from the teaching part of our missions, but that’s how we’ve built our institutions, so cuts in teaching revenue will hurt us.

Our research support teams budget is mostly salaries, and cost for equipment of various sorts. Like salaries, which go up (good), new equipment costs go up over time - reflecting the (also good) fact that their capabilities grow from generation to generation. So again, anything less than say a 5% increase in revenue year-over-year means a cut of people, or at very least a relative cut in capability of equipment.

And that’s just the teaching revenue.

New Zealand has slashed research funding for basic research (and zeroed out social sciences research in one of its major funding tools). The new UK government cut more than a billion pounds from technology and AI projects. Canada’s research councils are scheduled for a long-needed funding increase, but that will only happen after an election where it seemed quite likely at least until recently that a different party with likely very different priorities would win. As mentioned before, Australia’s going through some stuff, and I need someone to explain it all to me like I’m five because I just can’t keep track of it all.

And then, hey, did you hear there’s a new president in the US? The sudden and maybe?-now-unfrozen freezes in NIH and NSF, plus everything that’s going on with CDC publications, augers extremely poorly for the funding environment there. I think we can safely assume that international student numbers are going to plummet, as well, and for multiple reasons.

Yes, there’s other issues going on in the world and our communities right now besides the fate of our technical research support teams. But once we stepped up to become manager, our teams become our responsibility.

We care about our team members as individuals. We want them to grow as individuals and professionally and want to support them.

And we genuinely believe that funding and effectively operating teams like ours are one of the best and most cost-effective ways to advance research at scale for a world that desperately needs new insights and better ways of doing things. One of the things we can do to try to keep the world somewhat on its axis is to keep our teams going and advocate for their needs and ongoing work and impact.

Keeping our work funded is part of that. There’s other parts, too, especially for my US colleagues, like keeping morale up and supporting individuals. Today let’s focus on keep-the-wheels-on funding issues.

Funding for our teams is vulnerable because our business model is that of nonprofits (#164), even though our operating model is of professional services firms (or utilities - #127). There’s a million worthy things increasingly scarce research funding could go to, and we have to actively make the case for our teams (and even better, help others champion us) because other more visible efforts will always have the advantage of seeming more salient to decision makers.

That means:

These are febrile and challenging times in research institutions everywhere. If you have questions, want advice, or just want someone to vent at, you can always email me (hit reply or email jonathan@researchcomputingteams.org) or have a quick call with me. I want to know what I can do to help.

With that, on to the roundup:

Over at Manager, PhD in #178 I talked about systematically collecting qualitative data (which is useful too for those researcher and VPR-office calls!). Plus:

In #177 I talked about positioning yourself for a first-time manager job, plus:

RCD Program Story: Northwestern University - Daphne McCanse

Great writeup of an interview with Jackie Milhans at Northwestern, describing the work of Research Computing and Data at Northwestern University, how it’s structured, how it’s handled rapid growth, and how priorities are set and outreach is done.

Massively multiplayer retrospectives - Jade Rubick

As you know, I think retrospectives are to managing teams (Management 201) as one-on-ones are to managing individuals (Management 101) (#137).

Here Rubick goes through his process for retrospectives for remote teams, which he reports getting much broader participation from, while still being time efficient and useful. He makes use of Google Doc (or equivalent).

He has people have the first ten minutes or so contributing to a Google doc w/ 2 sections:

And that 10 minutes includes adding to (not contradicting, not arguing) others comments.

Then a round of dot voting with a handfull of votes per person, where they can add votes (with their initials, an agreed-upon emoji, whatever) to each of the points. Then the top ranked items are discussed, preferably with action items resulting.

The online/google doc aspect means that lots of people who would feel uncomfortable contributing vocally still contribute; it means important topics get covered deeply; it means less urgent topics are still voiced and documented.

I really like this approach and am going to find an opportunity to use it.

TBM 332: The Last Strategy Framework You’ll Ever Need - John Cutler

So you might have already heard that I’m very, very, very, very unhappy with what “strategy” is taken to mean in our community, and how we think about it.

And many of our teams are probably going to find ourselves thinking critically about positioning, prioritization, planning, problem solving, stakeholder engagement, and communication in These Challenging Times (tm).

There’s a sense in which that’s good - these are things that are important enough to be routine parts of our practice - but having to tackle in an emergency isn’t great. Sadly, that’s where many of us are, or will be.

And folks, “strategy” is not synonymous with SWOT charts.

So I want us to briefly talk about “strategy frameworks”. Cutler here has a very good article I’m frankly super jealous of, because I’ve taken a stab at writing something similar more than once and never pulled it off.

There’s nothing magic about any of these strategy frameworks. SWOT isn’t some kind high-powered tool that automatically produces profound insights. (I don’t have anything in particular against SWOT, but it seems to be the only thing that people in our communities have ever heard of.)

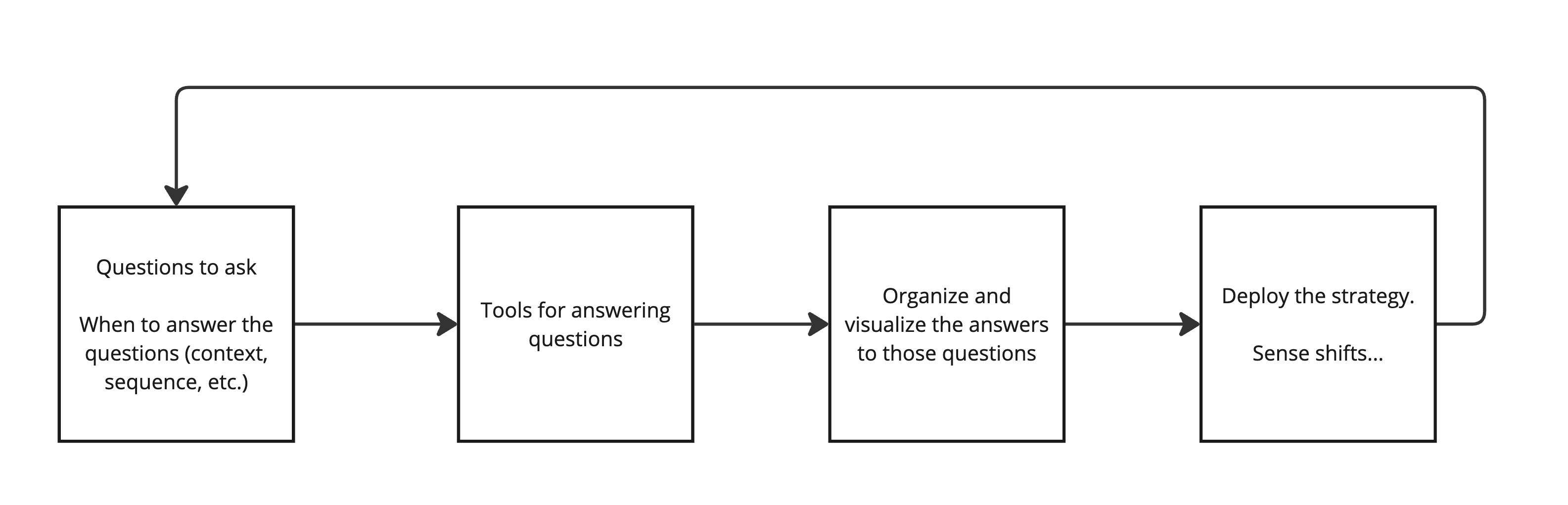

As Cutler points out, there’s four basic functions any of these of strategy frameworks have:

And they’re a loop.

Cutler iterates through several frameworks and shows how they fit those boxes. And as he says:

Strategy is not just about frameworks or decision-making tools; it’s about negotiating a narrative, identity, and power within the organization [LJD: or in our case, ecosystem]. It’s (ideally) about shifting to humility and accepting uncertainty (vs. an ironclad 50-page deck that tries to anticipate objections and squash them), which in turn enables adaptability and probabilistic thinking.

So if you start getting advice about using particular strategy tool, just assess its usefulness. Is it helping you find the questions that are valuable to ask? Is it helping you collect data that would assist you get answers to those? Is it helping you develop insights from those answers? Does it give you suggestions for how to actually make changes based on those insights? A tool that helps you do some of that can be very useful, even if others have never heard of it. A tool that doesn’t is a waste of time for you, even if it might be incredibly helpful to others in different contexts.

(Bonus link: here’s a set of strategy frameworks. FWIW I think the main ones that matter to us are value net for positioning, value chain/wardley map for clarifying operations, lots and lots of conversations with the VPRs office and researchers, and a risk register populated by gaming out lots of bad scenarios).

How biotechs use software to make drugs - Kenny Workman, LatchBio

This isn’t a project, really, so much as a description of a workflow, but I think it’s a really nice walk through as to how a hypothetical biotech developing antibodies for heart disease might use compute and data infrastructure.

Tales of Transitions: Seeking Scientific Software Sustainability - Johanna Cohoon, Caifan Du, James Howison, Proc. ACM on Human-Computer Interaction

This is an interesting seven-year study of 34 software projects (mostly NSF SI2 projects), how they were organized, and whether they managed to sustain themselves.

They categorized the teams building the software into five categories:

Peer production (e.g. community driven) software was much more likely to sustain itself (maybe especially if it was “born” peer-production? It’s hard for me to tell). Businesses doing the software kept the software active at a pretty good rate, too. Tool groups did ok; software from lab groups survived maybe 50/50, loose author groups or consortia survived at a much worse rate.

This is an interesting paper and I’ll try to dig into it more. I’d like to see more slices-and-dices of the data, although there may be worries about confidentiality at that point.

An unspoken assumption of some work like this is that all of the projects should survive, that going inactive is a failure. I don’t think that’s true. Some software is useful to a community which can collectively sustain it; some just isn’t. It’s ok for software to be a one-off! Writing some software for a research project, even a research programme, shouldn’t be a commitment on the lab’s part or on the part of the scientific enterprise as a whole to fund further development indefinitely. Just as not all research directions end up being fruitful, not all research software needs to continue existing.

On the other hand, for research funders, I think there’s a lot to learn here. Research funders giving grants funding software development, as opposed to funding research projects that happen to develop some software, presumably want to favour efforts that will outlast the particular project. My probably idiosyncratic takeaway from this paper is that such funding should preferentially go to existing software efforts that are community-driven or have a business model associated with them.

From the 100 Day Mission to 100 lines of software development: how to improve early outbreak analytics - Cuartero et al, Lancet

During a 3-day workshop, 40 participants discussed what the first 100 lines of code written during an outbreak should look like.

This is a fascinating read - my attempt to summarize it wouldn’t do it justice, and it’s a short read, so I commend it to you. Even more interesting is to think about how as research data, research software, or research computing teams, we could be ready to support those first 100 lines of code - and the work that follows.

LLM Training Without a Parallel File System - Glenn K. Lockwood

It’s surprising to me the extent to which people with HPC backgrounds assumes that a large, shared-by-everyone parallel file system is an absolutely essential part of a computing cluster, to the extent of reflexively introducing them into cloud clusters wherever they can. Global mutable state is hard and error prone, and I don’t ever think I’ve heard a researcher client say “one thing I really love about this system is sharing the file system with every other user”.

The instinctive assumption of any parallel file system surprises Lockwood, too, who knows more about parallel file systems and other large-scale storage on his worst day than I ever will.

Lockwood describes LLM training, and the role that preprocessing, object storage, and local SSDs play, with lots of diagrams and references to other posts.

As technologies and workloads change, it’s important that we focus on what’s needed and not just what we’ve always done. As Lockwood says, “But parallel files aren’t all bad…. I do not advocate for throwing out parallel file systems if they’re already ingrained in users’ workflows!”

But workloads and requirements differ, and the purpose of our systems are to meet those requirements and support those workloads, not just to replicate the same infrastructure we’re familiar with.

Let’s deprecate “cargo-cult” as a term our community uses. The use is inaccurate, fictionalized, and really uncomfortably problematic.

The free online “Fundamentals of Numerical Computing” book has a new edition and a Julia version, if you’re into that.

C’mon, admit that you want one of these fluid simulation pendants.

Doom running … in a PDF? Sure, why not.

Grist, kind of a typed spreadsheet/database kind of thing.

“Random Access” Memory is a myth.

And that’s it for another week. If any of the above was interesting or helpful, feel free to share it wherever you think it’d be useful! And let me know what you thought, or if you have anything you’d like to share about the newsletter or stewarding and leading our teams. Just email me, or reply to this newsletter if you get it in your inbox.

Have a great weekend, and good luck in the coming week with your research computing team,

Jonathan

About This Newsletter

Research computing - the intertwined streams of software development, systems, data management and analysis - is much more than technology. It’s teams, it’s communities, it’s product management - it’s people. It’s also one of the most important ways we can be supporting science, scholarship, and R&D today.

So research computing teams are too important to research to be managed poorly. But no one teaches us how to be effective managers and leaders in academia. We have an advantage, though - working in research collaborations have taught us the advanced management skills, but not the basics.

This newsletter focusses on providing new and experienced research computing and data managers the tools they need to be good managers without the stress, and to help their teams achieve great results and grow their careers. All original material shared in this newsletter is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0. Others’ material referred to in the newsletter are copyright the respective owners.

This week’s new-listing highlights are below in the email edition; the full listing of 361 jobs is, as ever, available on the job board.